Deepwater Fields Define Angola's Oil Wealth in the New Century

by Moses Aremu, Lagos

Contents

For most of the second half of the 20th Century, Angola's oil wealth was derived from the discoveries on the continental shelf. A quarter century of war had foreclosed oil exploration and production activity on most of the prospective onshore area and deepwater activity was far away in the future. Up until last November, a Chevron-led consortium produced 420,000 b/d oil, or 58% of Angolan production of 720,000 b/d from Block 0, in water depth ranging from 10 meters to 160 meters offshore Cabinda. Other companies: Elf, Texaco, Fina, Ranger, and the Angolan state oil company Sonangol produced the rest.

For most of the second half of the 20th Century, Angola's oil wealth was derived from the discoveries on the continental shelf. A quarter century of war had foreclosed oil exploration and production activity on most of the prospective onshore area and deepwater activity was far away in the future. Up until last November, a Chevron-led consortium produced 420,000 b/d oil, or 58% of Angolan production of 720,000 b/d from Block 0, in water depth ranging from 10 meters to 160 meters offshore Cabinda. Other companies: Elf, Texaco, Fina, Ranger, and the Angolan state oil company Sonangol produced the rest.

But since 1995, oil majors have started to encounter huge oil reservoirs in Angola's deep aquatory, from water depths of 300 meters to far beyond 1200 meters. Reserves have been in proportions far exceeding anything onshore. In half a decade, some eight billion bbl have been discovered. If three-quarters of these are proven, Angola's reserves will more than double from 5.4 billion to 11.4 billion bbl.

These deepwater finds are now being monetized: by Christmas 1999, Chevron had started production of the Kuito Field, in 350 meters of water, offshore Cabinda to bring the Angolan deepwater frontier full circle; from mere exploration "hot spot' to production zone. With 100,000 b/d gushing from the field, Angola joined Congo and Equatorial Guinea in contributing a total of 350,000 b/d or 25% of the world's deepwater production budget of 1.387 million b/d.

The Kuito start up, coupled with increased oil prices, is encouraging other majors to look closely at moving their Angolan deepwater portfolio from exploration to development stage.

Elf's Block 17(Back to Top)

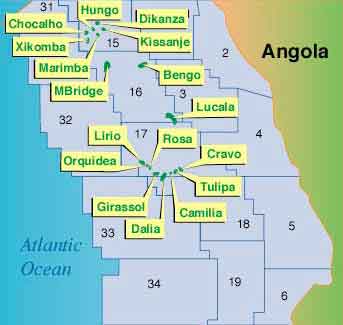

Angola's Block 17 has been a bonanza for Elf Aquitaine and its partners. Since 1966, when Girassol was discovered, five other fields have been found, Dalia, Rosa, Lirio, Tulipa, and Orchidea, and three prospects that are promising, Cravo, Jacinto, and Jasmin. Furthermore, 14 of the 15 wells Elf has drilled on Block 17 have been positive.

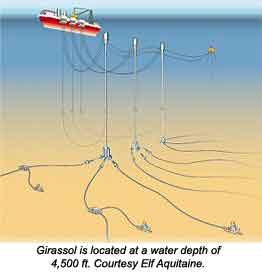

Elf plans to do exploratory drilling on Cravo, Jacinto, and Jasmin, which are in the block's deeper western section, by yearend, once its two new rigs arrive, according to Jean-Francois Gavalda, head of African E&P for Elf. The rigs, the drillship Pride Africa, and the semisubmersible Sedco Express, will drill 5-10 wells by midyear. (The Pride Africa is enroute from South Africa, and the Sedco Express is due for delivery within three months.) Having been previously stalled by low prices, complex geology, and new technology, Elf has gone back to the drawing board on Girassol, its flagship deepwater field. In April, the company will start drilling development wells aimed at getting them on stream with the Pride Africa drilling the first of the initial 20 producers needed to drain the field . The production—to what Elf says will be the largest FPSO to date—will start in 2001.

Elf discovered Girassol in 1996, while Chevron encountered the Kuito only a year after, in 1997. For this reason, some observers have said that Elf was rather slow in putting Girassol on stream. But the comparison between Elf's tentativeness in Girassol with Chevron's speedy start up of Kuito misplaces the emphasis—Kuito is merely a step out of Chevron's Block 0 operations offshore Angola. It was easy to develop a facility and tie it to the production inshore. On the contrary, Girassol is in 1350 meters of water, one of the farthest deepwater fields in West Africa. Elf says that its development will involve the largest infrastructure for such depths ever installed, as well as innovative technology. There will be: 40 subsea wells, of which 23 will be producing; 14 water injection and three gas injection wells. Production per well will range as high as 40,000 b/d; Girassol Field is 18 km long and 10 km wide, with a substructure of meandering sand complex with overlapping channels. The high reservoir quality allows for the drilling of few wells for efficient drainage. Facilities will be constructed simultaneously with early field development. The wells will be drilled from one semisubmersible rig and one dynamically positioned drillship. Together they will cost US$600 million. The entire bill is $2.5 billion. Chevron's cost of developing the Kuito Field has been far less than this.

There is yet no word about Exxon's plans for its much hyped series of discoveries in deepwater Angola. The best information we have is that the finds: Hungo, Kissanje, Mirimba, Dikanza, Chocalho, Xicomba, most of which are yet to be appraised, will be pooled together for production purposes.

Eighteen major oil finds have been made in Angola. One discovery that went wrong was Shell's Bengo Field in Block 16. Bengo-1 tested 1780 b/d in one reservoir, the first discovery in deepwater Angola. Shell's initial enthusiasm about the structure was restrained by the well's high gas cap and pancake thin reservoirs, but the company was willing to risk an early production. The enthusiasm died when Bengo-2 turned out to miss even the thin bed that was of such keen interest in Bengo-1.

Incidentally, the Bengo story had defined Shell's involvement in deepwater Angola. Whereas other companies: Elf, Chevron, Exxon, even BP Amoco, went on to make discovery after giant discovery, Shell got trapped in a run of ill luck, having drilled 9 wells in Block 16, most with marginal results.

This is curious, because Block 16 is located between the two most successful leases in the area, Esso's Block 15 to the north and Elf's Block 17 to the south. The last well drilled in block 16 was Chiluango-1 which was abandoned in early November 1998 as a dry well. In 1999, the company packed out of Block 16 and shifted its gaze to Nigeria where, by 1996, it had become sure of the deliverability of its huge Bonga structure, in the upper slope of the deepwater Niger delta. It is an irony that the world's leading deepwater exploration company would fail to get things right in the world's most prominent deepwater play.

This is curious, because Block 16 is located between the two most successful leases in the area, Esso's Block 15 to the north and Elf's Block 17 to the south. The last well drilled in block 16 was Chiluango-1 which was abandoned in early November 1998 as a dry well. In 1999, the company packed out of Block 16 and shifted its gaze to Nigeria where, by 1996, it had become sure of the deliverability of its huge Bonga structure, in the upper slope of the deepwater Niger delta. It is an irony that the world's leading deepwater exploration company would fail to get things right in the world's most prominent deepwater play.

The historic boost in oil reserves in Angola since 1996 is in sync with the period of successful deepwater activity in West Africa. The current buzz in the oil patch that the West African deepwater fairway is the most exciting exploration site can be almost entirely correlated with the events in Angola. In the first 10 months of 1998, deepwater discoveries in Africa totaled 13, nine of which were in Angola, three in Nigeria, and one in Congo.

Angola's operated leases cover 72,643 sq km, roughly 10% of the 718,000 sq km of "licensed" blocks in Africa's deepwater. For the country itself, it is a remarkable turning point. The 8 billion bbl discovered in deepwater between 1995 and 2000, represents two thirds of all the oil discovered since 1955. The "belief" in Angolan deepwater prospectivity encouraged majors to plank down $300 million dollar signature bonuses for the 1998 ultra deepwater lease bidding round.

Geology(Back to Top)

The Angolan deepwater fairway evolved as part of the geology of the entire West African segment of the south Atlantic, which involves roughly eight basins lining the coast, all part of a large linear trough, which has been subsiding, probably since late Jurassic time. It was then that the super-continent Gondwanaland divided into West Africa and South America, forming the Atlantic Ocean between them.(Previous discussions have listed six basins, sometimes some of these basins are mere fingers or extensions of the others. Most of the Angolan basins have featured salt diapirism, more than any basin in northwest Africa).

The Gondwanaland breakup is assumed to have been initiated in the Gulf of Guinea area, where a thick and extensive miogeoclinal wedge of sediment accumulated along the continental margin of West Africa. In Angola, there is the Kwanza Basin, which runs north to south along the edge of Angola; the Congo Fan, which lies parallel, on the seaward side of the Lower Congo Basin. It is the ultra-deepwater portion of the Lower Congo Basin, and comes across as if its was created by dumping sediments from the Congo River, which cuts perpendicular to the trend of the Lower Congo Basin. The Congo Fan, essentially a Tertiary development, is younger than the Gabon Coastal, Lower Congo, and Kwanza Basins, all of which are Cretaceous in age. Recent literature have featured the ultra-deepwater Namibe Basin, which is also extensively seen in Namibia seepwater.

The Salt Basin was initiated with the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous rifting of the super-continent Gondwanaland. Neocomian to Lower Aptian synrift fluvial clastics and lacustrine shales were deposited during the initial stages of separation of Africa and South America. The early post rift section is dominated by thick marine evaporites. Carbonates were deposited during the Albian. With continued seafloor spreading during the tertiary, a thick sequence of shales and turbidite sands were deposited.

Since the middle Oligocene, three agents have promoted deepwater sand deposition in the Lower Congo Basin. First, uplift of the West African coast has steepened the continental margin and exposed crystalline basement rocks at the basin edge and in adjacent fluvial catchments. Second, northward drift of Africa has caused the basin hinterland to pass from a climatic zone to a more humid one, promoting erosion and delivery of sediment to the basin. More; periodic glaciation arising from the evolution of the Antarctic ice cap, have significantly lowered and fluctuated sea level respectively, facilitating clastic transport into the deepest part of the basin.

The thickness of the post-rift, Aptian salts (those formed in situ) varies from zero to several km in the mid to lower slope (deepwater) of the Lower Congo and Kwanza Basins, where they influence the styles of the overlying structures. This variable thickness creates strong lateral velocity gradients and imaging problems. But comprehensive mapping techniques have revealed a set of major basement faults, parallel to the basin margin and generally stepping down to the west (seaward). The major development on these faults occurred during the rifting stage. The salts mark the boundaries between zones of different structural style and the movement of sediment sheath over basement generates growth synclines, whose architecture is controlled by the rate of sediment aggradation and the rate of downslope sliding.

Seismic profiles in the deepwater Lower Congo and Kwanza shows that the structures in the mid to lower slope are dominantly created by compressional folding, with subordinate salt-withdrawal and diapirism Oligocene and Miocene deepwater sands of the deepwater turbidite sands (Malembo Formation) currently are the main prospective intervals in the deepwater wells of the Lower Congo Basin (Congo Fan). This is where Girassol, Dalia, Rosa, Hungo, Belize, Landauna, and the rest of the big discoveries are located.

Seismic profiles in the deepwater Lower Congo and Kwanza shows that the structures in the mid to lower slope are dominantly created by compressional folding, with subordinate salt-withdrawal and diapirism Oligocene and Miocene deepwater sands of the deepwater turbidite sands (Malembo Formation) currently are the main prospective intervals in the deepwater wells of the Lower Congo Basin (Congo Fan). This is where Girassol, Dalia, Rosa, Hungo, Belize, Landauna, and the rest of the big discoveries are located.

Exxon has described the deepwater reservoir sandstones in the Lower Congo Basin as analogous to those in the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico, and suggested that the two are very similar. Exxon geoscientists say that they can provide useful insights into the likely nature and performance of the Lower Congo Basin deepwater reservoirs.

3D seismic data from the Lower Congo Basin indicate a profusion of bright, high-amplitude reflections in the late Oligocene and Miocene succession. These are interpreted to be deepwater reservoirs.

Observable signatures on 3D seismic profiles include uniform, concordant, and internally continuous reflections, frequently interpreted as overbank deposits. Conformable seismic reflections with constructive geometry, obviously different from those suspected overbank deposits, are believed to be leveed channels, resulting from the build-up of the levee crest above local topography. Linear, frequently erosive features showcasing internally discontinuous high amplitude seismic characters.

The Year 2000 (Back to Top)

Drilling is expected to rise sharply in Angola this year compared to 1999, when activity were reined in by collapse on oil prices. Beyond the deepwater Congo Basin, where much of drilling has happened operators will be looking to ultra deepwater Congo, the Kwanza Basin in southern Angola and the Ultra Deep Water Namibe. BPAmoco is almost completing 5400 sq km of 3D seismic survey in ultra deepwater Namibe Basin and will drill first well in the 5349 sq km block 31 later this year. Exxon Mobil is making a blanket 3D survey of 4000 sq km of Block 33, also in ultra deepwater Namibe Basin.

Texaco will take its first tentative steps in drilling in deepwater Angola. It will drill Goiaba-1 in deepwater offshore Kwanza Basin in June. This is a far journey to arrive for Texaco, which is spread very well in deep offshore Nigeria, where it is developing a 1.5 billion bbl oil field Agbami. (With the size of Agbami, and it's ownership in three other leases in deepwater Nigeria, it should be easy for a mid-size company like Texaco to forgo Angola entirely. But then the Angolan deepwater prospects are very tempting.

Texaco will take its first tentative steps in drilling in deepwater Angola. It will drill Goiaba-1 in deepwater offshore Kwanza Basin in June. This is a far journey to arrive for Texaco, which is spread very well in deep offshore Nigeria, where it is developing a 1.5 billion bbl oil field Agbami. (With the size of Agbami, and it's ownership in three other leases in deepwater Nigeria, it should be easy for a mid-size company like Texaco to forgo Angola entirely. But then the Angolan deepwater prospects are very tempting.

Texaco had spent a number of years studying geological similarities between Kwanza Basin of Angola and Campos Basin of Brazil. The company will apply the results in the drilling of the Goiaba well. Analysts forecast that exploratory drilling in deepwater Angola will rise by 33% to 40 wells in 2000 from 30 in 1999 as CAPEX rises to $4.13 billion from $3billion in 1999.

The next field to come on stream is Chevron's Benguela followed by BPAmoco and Exxon's start ups in 2003 to 2005. Together these should enable the near doubling of Angola production from 794,000 today to 1.5million b/d by 2005.