No Kill Fluids, Underbalanced, & Frac & Pack Redefine Perforation Design

Contents

Once a well has been drilled through its producing formation, assuming a commercially viable well, operators must choose between cased and openhole completions. Most modern wells are of the former variety, with pipe set and cemented across the producing zones. How the next step—punching holes through pipe, cement, and formation to drain the well fluids—is done is as critical to the well's performance as any other single operation over the course of the well's construction.

Basic Perforation (back to top)

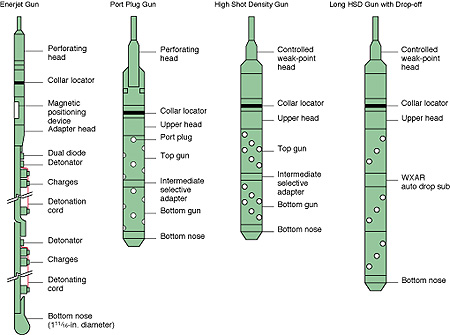

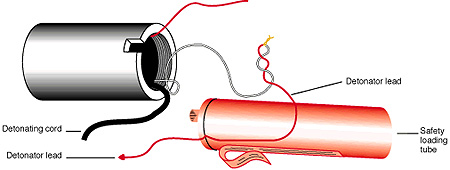

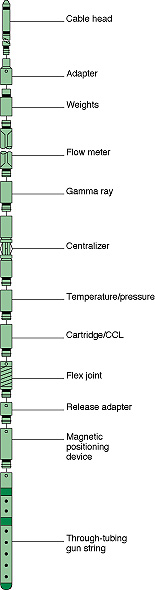

Punching those holes is called perforating and in its most basic form is a simple matter of lowering into the hole, on an electrical line, a tool loaded with shaped charges aimed perpendicularly out from the center of the well bore. Logically enough, the tool is referred to as a perforating gun. Once the charges are located precisely at a pre-determined spot (often, allowing only inches as a margin for error), an electric impulse sent along the wire causes the gun to fire, sending a charge into the rock to create tunnel-like drainage holes from which oil and gas flows to the well bore.

The vast majority of wells being perforated today are still done according to the above scenario. Typically, the guns perforate from about 10 to 30 ft of casing and rock length in each operation. If much more pay is to be shot, or as is most often the case, if considerable lengths of non-producing sections separate the intervals of interest, any number of runs may be needed.

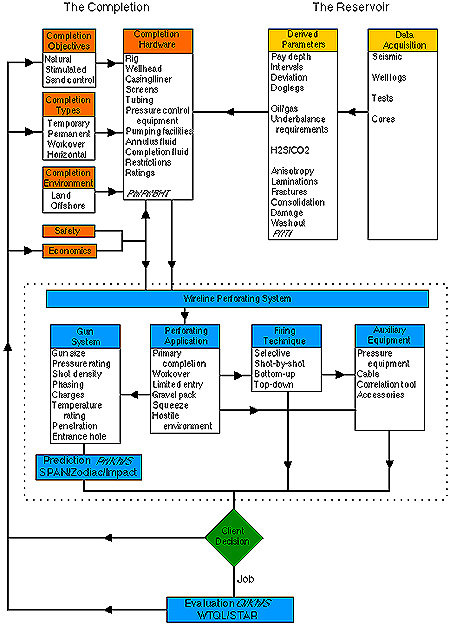

As is true with every other aspect of the oil industry during the past 15 years, the simple perforating operation has been refined by the technical advances around it, particularly in certain challenging cases. In its most rudimentary form, the most important perforating considerations are depth of penetration and diameter hole desired. (Contrary to what one might think, deeper and larger is not always the appropriate choice.) Now, the questions are just as likely to include choice of processes, reservoir conditions, and time considerations as well as gun type and size.

"Now operators want to do a variety of techniques for perforating," said Schlumberger's Dwight Peters. "A lot of people want to shoot 100, 200, 300 ft at a time. We have always been able to do that, but we had to kill the well to get everything out of the hole."

To "kill the well" the wellbore must be filled with heavy fluids to hold back the well's natural pressure. No matter how well that fluid is balanced, some inevitably flows into the reservoir rock. Even when the wells are treated and flowed back to surface until only well fluids appear to be coming out of the well, chemicals and materials used to lend weight to the kill fluids are left behind in the reservoir, plugging flow paths and hindering the well's ability to flow.

One answer to the damage of kill fluids is not to use them, particularly in highly permeable reservoirs where they flow easily and deeply into the producing formation. For years, companies have been drilling underbalanced, that is allowing the formations controlled flow even as they are being drilled. Now, to eliminate heavy kill fluids, perforating companies are doing the same thing and shooting the wells underbalanced.

"We have three specific engineering task forces doing [underbalanced perforating] right now for coiled tubing, wireline and tubing conveyed," said Peters. "You flow it back and clean up the well bore and shut it in and pull everything without ever using kill fluid so native fluid is the only thing in the well bore."

Underbalanced drilling which led to underbalanced perforating came into its own as an answer for how to drill through long horizontal sections of producing zones without damaging them with heavy drilling muds designed to hold back well pressure. So too has the explosion of super extended reach drilling brought a call for extreme-length perforating sections.

At the Wytch Farm Field in the UK, where BP has been making a science of setting extended reach records, drilling from land based rigs out and under an environmentally sensitive marine area, Peters reports his company has just perforated 8,000 ft of well in a single run. Since most of that length was through producing zones, nearly 25,000 charges were fired at one time.

Drilling in Offshore Areas (back to top)

In many offshore areas, particularly those whose production comes from highly permeable sedimentary basins such as those in the Gulf of Mexico, gravel packing has led to another new perforating practice. In those areas, sand is placed against the formation face to keep its unconsolidated sections in place as hydrocarbons are flowed through it.

Traditionally, once a gravel-pack candidate was perforated, the well was killed, the perforating guns and their conveyance (wireline, coiled tubing, jointed tubing) removed and a complex gravel-packing tool run in the hole. The time-consuming operation was not only a danger to the reservoir, leaving the formation exposed to damaging fluids for substantial amounts of time as it did, but in the high-dollar world of offshore drilling, it resulted in a lot of non-productive rig time at a very high cost.

In an attempt to shorten this down time, perforating companies have learned to run tools in the hole in conjunction with the gravel pack tool. Then, once the perforating guns have been fired, the guns are moved out of the way, the tool is shifted open and sand is pumped into place. The whole operation is completed in less time than would have been necessary to pull the perforating tools alone. And even that technique has been streamlined.

The sand pumped into a gravel pack is carried in an emulsion of gelled fluids that themselves can cause formation damage if they do not, as they are chemically programmed to do, break down and flow out from between the grains of sand they carried into place. In response to that potential problem, the single trip method has been carried yet one step farther.

"The newer technique is to frac-and-pack," Peters said. "You not only shoot it and gravel pack it, but you actually pump some sand back into the rock and break it mechanically. Then you pump some sand back into those cracks so that you get past any damage you caused when you were gravel packing."

Drilling in Hard-rock Country (back to top)

In hard-rock country, where fracturing is a common completion practice, open hole logs have been perfected that tell the direction of the rock's strength so operators can determine ahead of time in what direction the fracture will propagate when the rock is subjected to stress. Then, by orienting the perforating tool so the perforations run along the weaker lines, the fracture job can be done less expensively.

"If you can perforate in the direction the [fracture] is going to go you can keep the cost of you frac job down because you reduce the horsepower required to open the fractures," Peters said. "And a frac job is charged by the horsepower expended."

The bulk of perforating is still a matter of shooting holes of length and diameter shown by experience to be the most appropriate in any given field. But as the industry moves into ever more technically challenging areas, the properly selected perforation design can go a long way towards a less costly or more productive completion.